|

| A section of the Garman Blockchain |

To keep my 5th graders engaged at the end of the year in an ungraded Library-Technology class that meets once a week, I decided to increase the intellectual level… significantly. My co-teacher, the Librarian, shook her head and laughed when I shared that I intended to teach 10-year olds about blockchains, cryptocurrencies, and NFTs. Adults complain all the time about how they “don’t get crypto,” but these 5th graders picked it up quickly thanks to a blockchain role-playing game I created with just a google sheet and some creativity.

I knew I would never get 10-year olds to understand blockchains, cryptocurrency, and NFTs by lecturing at them, so I designed a game that runs on a homemade blockchain where students receive cryptocurrency and NFTs and can use them to succeed on class activities and assessments. Think of this as a role-playing game, where, by using their crypto and NFTs (to defeat bosses!), students come to understand this technology. In our discussions throughout the unit, students made insightful points about our homemade cryptocurrency and NFTs that applied perfectly to the debate in the tech world about the utility of blockchains. They also learned a lot about tangential topics like digital and financial literacy, intellectual property, and citizenship. Perhaps most importantly, students thought innovatively, creatively, and strategically about a new technology with the potential to change the world they will inherit.

Background

I am no crypto-evangelist. Frankly, I don’t see the practical use, and I can’t get over the environmental problems (not to mention all the scams). Regardless, blockchains are an innovative piece of technology and they’re fueling ambitious and optimistic projects that may have an impact on future technology. For example, evangelists want users to own and control their own data on a blockchain (e.g. NFTs) and they want to build new decentralized institutions (e.g. DAOs) that can check the power of the current tech monopolies. Whether or not these projects are here to stay, I want my students to 1) understand the disruptive technology that they may inherit and 2) start thinking innovatively and strategically about how they use technology in their lives. Again, I am not sold on whether and to what extent this technology will enter our lives, but there’s loads of capital and thousands of talented engineers trying to transform technology as we currently use it. It’s imperative for the next generation to understand this so they can embrace the good pieces and push back on the bad. After all, had citizens better understood the last round of companies that “disrupted” our information ecosystem–companies like Facebook/Instagram and Google/Youtube–we could have better resisted the ad-driven business model that thrives on stealing our data and feeding it into an algorithm designed to hook us by amplifying our anxiety, anger, and fear.

Blockchain

With help from a colleague, I coded a Google Sheet to function like a blockchain, and then I launched our game with a loot drop (think: opening a chest in a video game) where every student acquired currency, called Garmans (named after the Head of School), and NFTs. The NFTs were items to be used in our role-playing game (e.g. Volcanic Battle Axe). Students received a wallet number that appeared on our public ledger/blockchain. They then created “character cards” based on the items in their wallet (Garmans and NFTs). They took these "characters" on quests–creative, fun challenges in faraway lands with mythical creatures–in the hopes of winning more loot and enhancing their characters.

The Google Sheet served as our “public ledger” of all transactions on our Garman blockchain. Students could buy, sell, or trade Garmans and NFTs with a simple Google Form. Much like a real blockchain, in order for the trade to go through, a “miner” (another student), had to verify the trade. For example, if one player wanted to trade her “Salmon Spidey Sticky Fingers” to another student for his “Golden Invisibility Cloak,” they would fill out the Google Form and enter their wallet numbers. The Form was connected to our blockchain and it auto-generated an email that went to a random student in the 5th grade who had to then verify, or “mine” (a crypto term for verifying a transaction), the trade in order for that exchange to appear on our public ledger. I incentivized “mining” the same way real cryptocurrencies do by releasing Garmans to miners that verify transactions. And I incentivized trading to acquire more Garmans and better NFTs because it helped them succeed on quests! If this sounds confusing to you, that simply highlights one of the biggest problems with crypto! People don’t get it. But I can assure you that my students figured it out quickly. Whether students were trading, mining or questing, they learned intimately how this process works. Students checked the public ledger frequently to see which wallet numbers were trading which items for how much.

After just one class, the Garman blockchain set off a wave of excitement and activity that spanned far beyond my classroom. Students raced to collect NFTs from the same “set.” They designed intricate characters with names, classes, backgrounds, and even signature outfits. And they asked dozens of questions about how this works, why, and what we can do with it.

Quests

In addition to administering a functioning blockchain, I also wanted this experiment to serve as the engine that drove my class throughout the 4th quarter. I designed a number of quests where students teamed up and used their characters to complete challenges. The first quest was essentially a creative quiz about the content we had been learning in this unit. Not only were students using our blockchain to design and modify their characters to succeed on this quest, but the questions that comprised the quest were about blockchains as well. For example, characters couldn’t get past a mythical wardrobe (and into Narnia) if they hadn’t made or verified a trade. And they couldn’t see the final boss in the mirror (from Alice in Wonderland) if they hadn’t shown creativity by writing their character’s background and by adding original work to their character card (to signify the NFTs they owned). If students succeeded, they had a chance to earn additional loot for their wallet and thus their character. Throughout the quest, I used different gamification elements to keep students engaged and challenged. One great thing about a gamified unit is students can fail at the game and learn from it without the fear of a bad grade!

The students were so engaged in the unit that they asked for more quests, more Garmans, and more NFTs. I overheard students trading Garmans for skittles at lunch. I had students emailing me throughout the day asking about a trade verification or seeking to purchase a new NFT from the Fox Shop (my storefront for selling new NFTs–also accessed via Google Sheet & Form). Though my class only met once a week, students interacted with our blockchain daily. As an educator, I harnessed this extracurricular energy, creativity, and collaboration for deeper learning. I sought other 5th grade teachers and asked them to share with me the content they were teaching. I turned this content into additional quests. Over the subsequent weeks, my Library-Tech class became a place where students completed quizzes for other courses all while learning the content and skills I set out to teach and refine at the outset of the unit–skills like creativity, collaboration, and resilience.

Examples

In the Math Menagerie, students had to apply their math skills to defeat their math teacher–an elf that lived in a tree that looked suspiciously like it came from the Keebler world. If they could calculate the perimeter of a stump, they could use it to cross a river (and they could use their NFT boots or gloves to climb or wade). In order to defend themselves from arrows coming from above, they had to know about isosceles triangles (and they could use their NFTs to return fire or heal each other if they failed the geometry questions!). And to get up into the tree, they had to know about greatest common factors. Clearly, this is a math quiz, but the students didn’t see it that way; they were questing, desperate to know what loot they could acquire upon completion.

|

| Math Menagerie Quest Example |

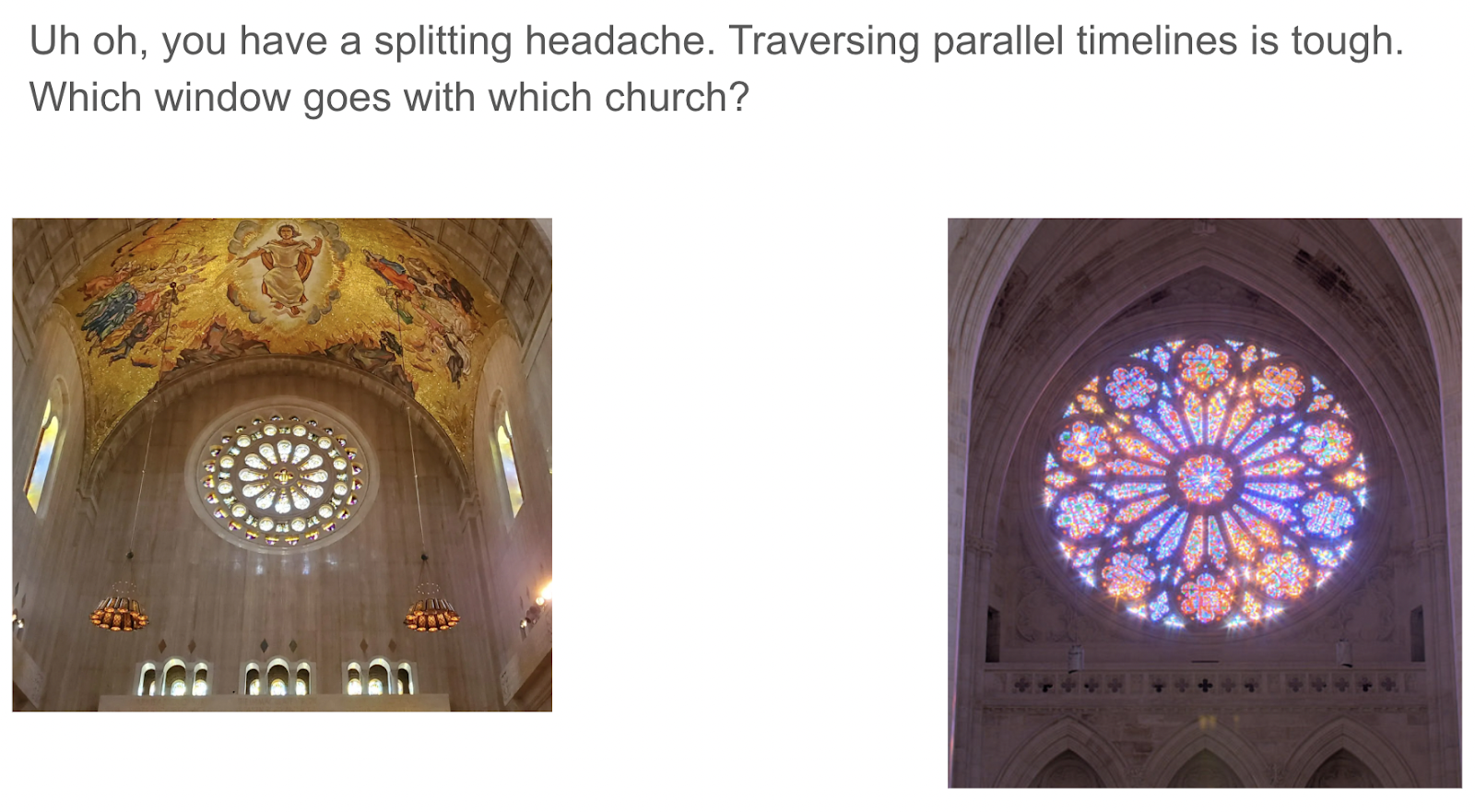

In the Church Championship, students used their knowledge of Romanesque and Gothic architecture to defeat a time-traveling cleric–their social studies teacher. If they got it wrong, they were locked in faraway churches and couldn’t help their teammates.

|

| Church Championship Quest Example |

I invited my colleagues to observe these quests, especially the ones with their class’s content. They couldn’t believe it. Students eagerly formed groups and sent their characters on quests seeking adventure and loot. It didn’t matter the subject-matter, this blockchain sustained teaching and learning for an entire grade level!

Creating these quests took skill, knowledge, and creativity, so I finished the unit by having students create their own quests about a topic they were passionate about from their 5th grade curriculum. The results were fun and exciting, but also insanely creative in a way that only 5th grade teachers will understand. They taught me new ways to use the blockchain that I created! This unit had something for all students to enjoy: teaching classmates about a passion, challenging friends with an evil (or nice!) boss, and doling out loot on the Garman blockchain. A seriously diverse group of students thrived on this project and many asked to create more!

|

| Student Quest Example |

Throughout the unit, I hosted brief discussions at the beginning of class before we started questing that encouraged students to think critically about the technology itself. The most illuminating discussion was when I asked, “what are Garmans worth?” and stepped aside. Inevitably one student would note, correctly, that this is all a simulation and Garmans weren’t worth anything. But another would point out that they were able to leverage their Garmans to get something they wanted, whether an NFT on our blockchain or Skittles on the playground. When students were waiting for trades to be verified we had a detailed conversation about bitcoin miners and the negative environmental impact of cryptocurrencies (my students were none too pleased). I also received a number of emails about a “scam” where one student took advantage of others via the trade Form. This led to a real conversation about how hackers and scammers take advantage of the anonymity of cryptocurrencies and also how they exploit the complexity of cryptocurrency and blockchains.

This game allowed students to experience sophisticated technological and economic concepts in a way that sparked engagement and provided a depth of learning that I didn’t know was possible with 5th graders.

The game mechanics allowed students to take ownership of their learning. They felt empowered by creating and participating as unique avatars while they also felt like they were part of something joining up to defeat bosses and creatures in imaginary places! All of this was documented on a public ledger, which means that it transcended my individual classes and pervaded the whole grade. Conversation about our blockchain permeated every 5th grade classroom/teacher to the point where I had to address it at a team meeting; “if you are wondering what the Garman blockchain is, ask a 5th grader!” Students were all too happy to teach their teachers (and parents) about blockchains, cryptocurrency, and NFTs.

I challenged students with tough material–learning about blockchains, cryptocurrencies, and NFTs–while also challenging them in the individual quests in a way that would have yielded stress and frustration in a normal class with quizzes and grades. But I learned that when students engage with a simulation / gamified unit, excitement and creativity quickly replace stress and frustration.

Our blockchain was self-sustaining, holding students' attention for a full unit inside and outside my classroom. The quests proved that these game mechanics worked in all 5th grade classes, not just my own. That left me wondering… what we could have done with this blockchain if every teacher designed a unit around these game mechanics/incentive structures. That would be something!